The Role of Music in Bangladesh’s Liberation War

Musician Naveed Stone asks the question why Bengali parents discourage musical careers when music has been an integral part of our culture and history.

By Naveed Stone

@NaveedStone

Movie Poster for “Muktir Gaan”, 1995 (The Song of Freedom)

When many of us grew up being encouraged to pursue careers in engineering or medicine and discouraged from pursuing the arts, it doesn’t quite add up when we see how much our parents clearly have an appreciation for music, art, and film. We grew up seeing our mothers unwind after housework with natoks on blast, hearing Bangla and Hindi music sung around the house, watching all the Bollywood movies. Next time they tell you to pursue something more “realistic”, tell them to imagine if all their favorite musicians and actors never spent their lives honing their crafts, pursuing their respective industries, and chose to play it safe and become doctors instead…

As an aspiring musician myself, it is very gratifying to learn about my people’s deep and historic appreciation for music. As we celebrate Bangladesh’s victory in the Liberation War of 1971 this month, it is important to understand how instrumental (pun intended) music was in getting our people through the most devastating time in our history. In a time when radio was the only main media source that reached everywhere in Bangladesh, inspirational voices and songs were spread by Shadhin Bangla Betar Kendra (Free Bengal Radio Centre). SBBK was the center of Bengali nationalist forces during the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.

SBBK was established by the Bangladesh government in exile soon after the declaration of independence in March 1971. It later shifted to Calcutta where it started airing regular programs from May 1971. Some of its popular programs were Chorompotro, Jallader Darbar and Bojro Kontho. Many Bengali singers and artists joined the SBBK, and performed memorable songs like Joy Bangla Banglar Joy, Purbo Digante Surjo Uthechhe, Ekti Phoolke Bachabo Bole, Salam Salam Hajar Salam – all of which we continue to sing 50 years later.

The SBBK singers were known as “Voice Soldiers” since they fought with their songs instead of weapons. The documentary Muktir Gaan, which is based on a group of singers from SBBK, gives a moving account of the singers’ contributions to our Liberation Movement. The group used to travel all day to refugee and Mukti Bahini camps to sing songs of motivation and encouragement.

The many singers of SBBK not only inspired our freedom fighters with their patriotic songs, but also mobilized to financially assist freedom fighters and Bangladeshi refugees. One of the “Voice Soldiers” Timir Nandy recalls in a 2019 interview:

“I would go to various places and inspire people including freedom fighters by singing mass songs. We also organized a group called Refugee Artist’s Group…we would deposit the sums that we collected from programs in Freedom Fighter’s Welfare Fund.”

Some of the singers from SBBK meet for a conference at The Daily Star, Dhaka. Source: The Daily Star Centre

However, despite the admiration and appreciation for these singers at all levels of society, the government did not adequately support many of them financially. Singer Abdul Jabbar has said many singers and staff of SBBK were not recognized despite their contribution to Bangladesh’s liberation, struggling to make ends meet for many years.

Learning how Bengali society fails to properly support artists even during a critical time in our history when musicians helped get our people through war, it is clear to me there needs to be a cultural shift in our attitudes toward artistic careers. As I’ve learned about the Liberation War through my dad’s first-hand experience, I can only imagine all the trauma that generation must be suppressing. I suspect that’s why they choose not to remember what a pivotal role music had in motivating them through such a perilous time. Nonetheless, it is up to us as the next generation to push Bengali culture in a direction that properly recognizes the value of the arts. That responsibility falls on us first-generation Americans because we have much more opportunities to chase our dreams than our parents did.

Speaking from that place of privilege, we make money to live. We don’t live to make money.

Read More

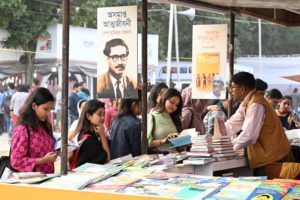

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More