Is Social Capital the key masala to Bengali Entrepreneurship?

BoNY founder, Kamrul Khan, explores Bengali entrepreneurship in the diaspora and how the older generation tapped into a valuable resource to jumpstart their entrepreneurial journeys.

By Kamrul Khan

Who needed law school?

Many of us were completing government documents for our parents at 8 years old.

We read prescription and dosage instructions to our parents like a pharmacist before we could walk to the pharmacy by ourselves.

Yet, many of them were able to start businesses, and scale, without having a full grasp of the English language.

Sure, today there many hip new restaurants and businesses being opened by 2nd generation Bengalis but think about all the Bengali owned grocery stores that existed in Jackson Heights, Jamaica or Kensington before our time. Many of those owners did not attend school here, they worked hard, took risks, and created successful businesses that allowed their children to go to college to complete an education.

Part of their success stemmed from the build-up of social capital that were nurtured in their close-knit communities (and may have roots in their villages or cities in Bangladesh).

This social capital consisted of personal ties established by implicit moral contracts, which lent itself to long-term relationships of mutual commitment and loyalty; the proverbial “I scratch your back and you scratch mine”.

This was evident in trips to the Bengali stores as a kid where, in addition to purchasing the meat and fish that were only found in Bengali stores, my dad would also purchase items that were available at “American’ stores at a lower price-point.

Why pay more at the Bengali stores? Because we were in it together.

These relationships turned ethnic resources into funding more entrepreneurial activity. They materialized into tangible tools such as financing and physical assistance in setting up a business. Or intangible assistance in the form of information, advice and guidance.

We all know that financing difficulties hinder many entrepreneurship goals, but a network of mutual trust helped facilitate financing.

Growing up in a building with mostly Bengalis, I remember this informal saving mechanism where the members would all pay a certain amount to the savings “pot” and one person would be given the entire pot, and then a different person would receive the pot the next month and so on.

Programs like these allowed those in the community to start businesses or pay for trips to Bangladesh. They were not required to pay and if they missed a payment, it wouldn’t hurt their traditional credit score, but it would hurt their Social Capital, so most would pay. The standing in the community and Social Capital was as important, if not more, than actual credit that could be used to obtain a loan from a Bank.

This Social Capital allowed for the risk to be shared among a community instead of focused on one individual. This acted as a risk-mitigant.

None of this is foreign to Bengalis (and all immigrant groups) since the idea of migrating to another country itself constitutes a high-risk situation characterized by uncertain income, and significant social stress but yet again is mitigated by the community enclave that many immigrants initially move into. Many Bengalis left secure jobs in Bangladesh, sold land and homes and this alone show the level of risk tolerance that exist in the immigrant mindset.

If Bengalis were able to create and have such success in their own entrepreneurship journey, then why do Bengali parents dissuade many from starting their own businesses?

Perhaps it is the lack of Social Capital among 2nd and 3rd generation Bengalis.

Perhaps it is the idea of uncertainty that is still something many of our parents don’t want us to face.

Instead, they want us to go to college in search of “stable” jobs that do not necessitate access to the Social Capital that was so integral to their own success.

Despite many immigrant parents’ wishes, the reality is that children of immigrants are much more likely to create businesses than the native-born population. Immigrants don’t come to this country to take jobs, they are overwhelmingly the creators of jobs.

Those that have seen our parents build successful business may not be able to tap into the same Social Capital they did but it is the characteristics of trust, honesty, and community that allowed them to flourish in it. It is those characteristics that, when applied, can allow 2nd generation Bengalis to build successful businesses today. We are in an opportune place to be even more successful entrepreneurs than our parents’ generation. We owe it to them.

Read More

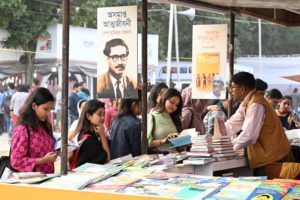

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More