Domestic Violence in the Bangladeshi Community:

The Murder of Arnima Hayat

Domestic Violence in the Bangladeshi Community:

The Murder of Arnima Hayat

By Bushra Mollick

@bushramollick

Headlines rocked shockwaves across Australia and Bangladesh following the brutal murder of 19-year-old Arnima Hayat. The aspiring surgeon was found decomposed in a bathtub of acid, following a welfare call to Sydney police. Her husband, 20-year-old Meraj Zafar, is currently in custody and has been charged with her murder.

Hayat was second-year medical student at the University of Western Sydney. She and Zafar were together for a short period of time before getting married, despite the disapproval of their parents. According to Australian reports, Hayat’s parents reportedly lost contact with their daughter shortly after she moved in with her husband. She was killed just four months after getting married.

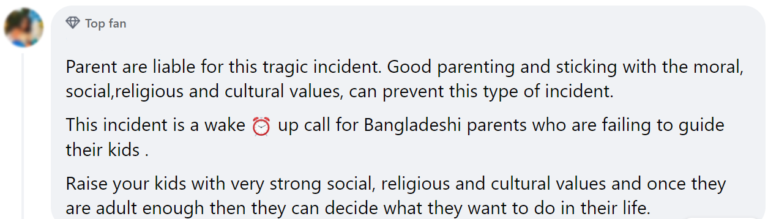

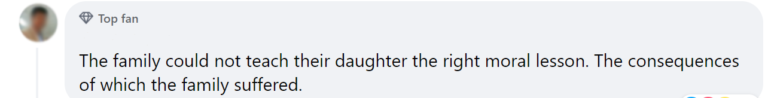

News video of her distraught and distressed parents went viral. As Bangladeshi media outlets covered her death, some speculated that Zafar was her live-in boyfriend, and not husband, leading to a myriad of verbal abuse across social media. Many commenters resorted to victim-blaming, citing lack of parental guidance as a reason for her untimely death. Others poked fun at the ethnicity of Zafar, who is of Pakistani origin. Below are just some of the common sentiments:

The victim-blaming and negative commentary Hayat received posthumously is not uncommon in Bangladesh or South Asia. Many victims of domestic violence [DV] seldom come forward due to denial, shame, and lack of resources.

Denial

Robina Niaz is the founder and executive director of Turning Point for Women and Families, a nonprofit with the mission to “help Muslim women and girls affected by domestic violence to empower themselves and transform their own lives, as well as those of their families.” Niaz is an activist and social worker who has offered domestic violence support within the Muslim community for more than three decades. She is also a DV survivor.

“What my experience tells me, is that the incidence of domestic violence and gender-based violence is no less, and, no more, than in all other communities. The issue and the challenge we face is there’s a lot of denial around it. There’s a lot of silence..a lot of denial about the prevalence of domestic violence in our community. And what that denial does, it actually hinders the victims from getting the help that they need…we tend to pretend that everything is hunky dory, and every Muslim family is healthy and functioning really well. However, that is not the case. Otherwise, we wouldn’t be doing this work.”

Turning Point for Women and Families is the first organization dedicated to supporting Muslim survivors of domestic violence in New York City. “The silence and denial in the community actually prevents survivors from seeking help, even from organizations like ours,” Niaz said, “We are based right in the heart of our community and rooted in it. We give all of ourselves to this work. And what is it that stops women from reaching out? It is the fear of being judged, shamed, and blamed for drawing attention to the abuse they face at home.”

Annesa Tabassum is a psychiatric nurse based in Austin, Texas. Readers may recognize her from her viral Tik Toks, shedding light on her own experience with domestic violence. “We use denial as a means to not leave or give the marriage another chance. My first thought was, ‘You know what? This isn’t really happening. I just got married. I need to stay married.’ These things can happen in marriages, but hey, I got married. That’s like an extra level of seal, I can’t just leave, it’s not just a breakup,” she said. “The denial keeps us into the marriage, and then even when we’re out of it, a lot of people don’t want to talk about it, or they want to pretend it never happened.”

Denial not only plagues victims of domestic violence, but affects the South Asian community as a whole, as well. “The only time domestic violence in our community hits the headlines is, God forbid, when someone gets murdered. And it’s not that murders are happening only in our community, but when that happens, the imams, the Muslim leaders, everybody is up in arms, trying to defend Islam” Niaz said, “They give interviews to the media saying, ‘this is not what Islam is about.’ They’re not worried about the woman who just lost her life or others who are at risk of the same. Their focus often is not on raising awareness around domestic violence or encouraging survivors to seek support but rather to defend the image of the Muslim community.”

“”Why is everybody worried about Islam looking bad? If you don’t want to make Islam look bad, then you must demand a change in behavior. You must address the issues in the community directly, by encouraging dialogue and developing effective programs. You hold the people who are committing crimes against women and children accountable,” Niaz continued.

Shame and Barriers

Even with denial, there are varying levels of barriers that limit victims of domestic abuse to come forward. Navila Rashid is the manager of training and survivor advocacy at HEARTtoGrow, a nonprofit organization dedicated to advancing “reproductive justice and uproot gendered violence by establishing choice and access for the most impacted Muslims.” HEART in HEARTtoGrow stands for Health, Education, Advocacy, Research, and Training.

“There are multiple barriers to disclosure, that can start at the individual level that then extends to familial, to community, to legal, to systematic, to institutional,” Rashid said, “Language is a barrier. And then on top of that, Bangladeshis have been conditioned, especially Bangladeshi women have been conditioned to believe that, for example, if they are married, that whatever violence and abuse they are experiencing, they just need to tolerate it. When you’ve been conditioned for that long, disclosing the violence in and of itself is a barrier because there’s a lot of self blaming that happens.”

Additional barriers to accepting help and resources can include financial restraints, immigration status, and limited access to the internet. Shyda Rashid is the anti-violence program manager at Sakhi for South Asian Women. Her day-to-day role includes monitoring the Sakhi helpline. The majority of her clients are Bangladeshi women.

“Our majority clients, they have conditional Green Card…I observed many times that they always receive the immigration threat,” S. Rashid said, “ So, they refuse to seek help from friends, family and community resource. They do not know about the legal system in this country that they can qualify for VAWA [Violence Against Women Act] and other legal options.”

Victims of domestic violence are often sheltered from movement in their own cities. Because many of the wives rely on their husbands for financial support, they are unfamiliar with everyday tasks due to the isolation. “If you just consider that domestic violence also exist in South Asia, even in Bangladesh, like most of the homes, they have the domestic violence issue, but they have the support system, family, friends. But in U.S.A., I found that most of the cases survivors are so isolated from their family, friends, community and that makes them more vulnerable,’ S. Rashid said, “So many clients that I have seen, they are living in United States for a long time, but they do not know how to navigate [the] MTA or how to call 911.”

Support and Resources: How to Help

Domestic violence can affect everyone in close proximity, including those who know of the violence. Being a domestic violence victim can be very isolating, but there are resources available. “How do we first take a deep breath and be survivor and victim centric and say, ‘Okay, how do we talk to the [victim]? And actually first hold that space and listen to them, and then ask them what they need? So, that’s the first step,” Rashid said.

As a survivor of DV herself, Tabassum suggests supporting as an ally. “”Hey, that I’m here, and if you want to think of an escape plan, it can help you. I have resources. I’m never saying you have to use this. I’m saying it’s here for the day you need it.’ That’s definitely what I would say to somebody who’s going through something even remotely similar.”

The murder of Arnima Hayat serves as a painful reminder that domestic violence and intimate partner violence still plagues South Asian communities. Though her story ended in tragedy, others do not have to.

If you, or someone you know, are a victim of domestic violence, please call the National Domestic Violence hotline: 800-799-7233. Additional resources are available.

Turning Point for Women and Families

Mayor’s Office to End Domestic and Gender-based Violence

Domestic and Gender-Based Violence Support

A Note from the Writer:

I witnessed my father abuse my mother for more than 20 years. She finally found the courage to leave when she was 47. It was incredible to watch her walk away, but disappointing to listen to some of the hearsay in the community. Regardless, she is alive and still with us. Her story, and the stories shared in this piece, remind us never to give up, to walk away, and to know our worth. Domestic violence, and intimate-partner violence, regardless of your gender, is never acceptable. Help is around the corner.

Read More

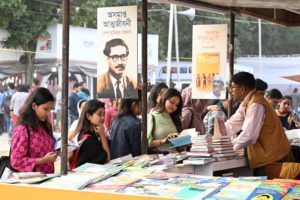

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More