The Pink Palace of Dhaka

The

Pink Palace of Dhaka

BY

ZARA KABIR

Ahsan Manzil facade by John Pavelka

Once the home of the Nawabs of Dhaka, Ahsan Manzil stands today as a beautiful reminder of Bangladesh’s ugly colonial past. Its walls were witness to many events from Partition to the ouster of the Nawabs to the establishment of a museum in the present day.

The vibrantly colored mansion, known affectionately as the Pink Palace, was built in the late 19th century. Located along the banks of the Buriganga River, the residence was a symbol of the affluence of Bengali aristocracy during the days of the British Raj. With the use of marble, ceramic, and wood to create decorated stairs and an artificial vaulted ceiling, it’s no doubt that this was a unique building in Old Dhaka at the time. This extravagant architecture boasts a mostly European influence from Greco-Roman columns as well as its archways and infamous dome.

This was not by accident. The British influenced almost every aspect of life in the subcontinent, including notions of wealth, power and status. While older architecture a couple of centuries before would have reflected more Indian and Mughal influences, the arrival of the British changed much of that. For the Dhaka elite, emulating European dress and manner of speech to separate themselves from the common folk of their country, seemed only natural. It is thus, no surprise, that this practice extended to the building of ostentatious homes.

Ahsan Manzil was no exception; in fact, it was the premier example of the snobbery of the upper echelons of Bengali society. Nawab Khwaja Abdul Ghani expanded his family property further following the death of his father. In 1859, he commissioned the building of a new palace. Ghani chose the name Ahsan Manzil after his son, Khwaja Ahsanullah.

Before the Nawabs, the property had originally been the garden house of Sheikh Enayetullah, a local zamidar or landlord during the Mughal era. Here, he built the original Rangmahal, which still exists today in a part of the Ahsan Manzil complex. The former would become known as “Ondor Mohol” following the completion of Ghani’s “Rangmahal”.

The name rangmahal itself has an interesting origin. With roots in Persian, rangmahal figuratively means ‘sandcastles of desires’. A fitting name perhaps, as it is said that Enayetullah enjoyed the company of many girls in his palace, lavishing them in dresses and bejeweled ornaments. One of these girls would capture the eye of the foujdar or Mughal representative, of Dhaka.

Out of jealousy, he conspired against the zamidar, inviting Enayetullah to a party to only kill him on his return back home. Rumor had it that the girl at the center of the bloody love triangle later committed suicide from the shock, sorrow and anger.

The property was eventually sold to French traders in the mid-18th century by Sheikh Motiullah, the son of Sheikh Enayetullah. Prime real estate with the location of the property so close to the Buriganga River, the French quickly set up a trading house on the land. Beside the building of their own palace of sorts, the French also created a beautiful pond, “Les Jalla,” which still exists today.

For almost a century, the French attempted to maintain control of their assets in Dhaka, as British influence continued to grow on the subcontinent. Eventually, they were pushed out and forced to sell all their properties. It was in 1830 that the first Nawab of Dhaka, Nawab Khwaja Alimullah and the father of Abdul Ghani, acquired the complex that would go on to become the Ahsan Manzil we know of today.

Throughout the rest of the 19th century, Ahsan Manzil saw many important developments. The Nawabs’ daily court and legal affairs were held at the palace, as well as meetings by members of the anti-Congress movement in Dhaka. The All-India Muslim League would eventually be founded as a result of the flurry of activity undertaken with the permission of Nawab Ahsanrullah who, it is reported, was himself deeply impassioned regarding the causes of Muslims groups at the time.

So important was the Ahsan Manzil and the Nawabs’ political influence in East Bengal, that British Lords visited the palace on numerous occasions. Lord Northbrook, the Governor General of India, visited in 1874. Lord Dufferin followed in 1888 and Lord Curzon, in 1904.

The Ahsan Manzil fell into disarray following the death of Ahsanullah. For much of the first half of the 20th century, the palace rapidly declined as the Nawabs could not afford to manage the property. Forced to rent out rooms from the once exclusive estate, Ahsan Manzil, suffered much damage to its interior. At one point, many impoverished people were living within the palace, which had been largely abandoned by the late 1960’s.

With the end of the British Raj in 1947 and Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, the descendants of the once mighty Nawabs had lost almost, if not all their influence. In 1974, they decided to sell the property as many of the family members moved abroad.

The Government of Bangladesh, recognizing the historical and cultural significance of Ahsan Manzil, have restored much of the interior and exterior parts of the palace. In 1992, Ahsan Manzil was opened to the public as a museum. It has become a popular tourist attraction, with its beautiful gardens within the estate as well as the palace’s bright pink walls and grand architecture, making for a picturesque location.

In the past, Ahsan Manzil was a place of opulence and frivolity as much as a place of great change. Today, this grand palace of Nawabs serves as a window into a past of bygone times and as a reminder of the fleeting nature of status and wealth.

Sources:

“Ahsan Manzil.” Banglapedia, 18 June 2021, https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Ahsan_Manzil

“Ahsan Manzil.” Beautiful Bangladesh, https://beautifulbangladesh.gov.bd/loc/dhaka/3.

“Ahsan Manzil – Bangladesh Science Foundation.” Bangladesh Science Foundation, https://www.bsf.org.bd/bangladesh-an-overview/ahsan-manzil/

Read More

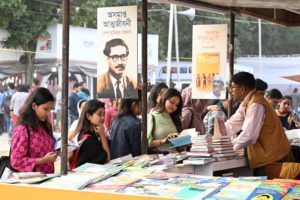

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More