What’s Your Name? The Real Question for Bengalis

In our luscious Bengali culture, most individuals are born with two names, one that is their official name, inscribed on their birth certificates while the other is inscribed in their being. Most to all Bengalis, regardless of religion, are given a daak naam or “calling name” that senior relatives will address one by. Daak naams are generally used only in the presence of family, at home, or with those with whom one is very close with; to the rest of the world, one goes by their bhalo naam or good/official name. These Bengali nicknames, then, can be seen as a “secret name” as only a select few will know it, giving off this sense that Bengalis have two identities.

In 2018, I conducted a preliminary research study focusing on the impact having a daak naam, or the lack of having one, has on one’s social interactions, with this post’s title being the study’s namesake. It focused on three main questions that would provide insight into deeper, more specific inquiries. These questions included 1. which social situations determine the preferred name to go by and how does this reflect on their behavior? ; 2. Is there confusion over where one should be A (daak naam) or B (bhalo naam)? How are the conflicting identities settled? ; and 3. does having a nickname make someone feel more Bengali?

Whilst having a daak naam of my own, the root of this study came from my personal conflicts with my two personalities: Ivana and Loudmila. Before kindergarten, I was solely Ivana, and she was the only one who existed in my identity. But, once school began, I was told I had to go by my ‘real’ name, Loudmila, and I didn’t understand why I couldn’t just go by the identity I associated with up till that day. Once school began, Loudmila appeared, and she was a girl who hated her first name as everyone continuously made fun of it while beginning the issue of butchering said name — I couldn’t blame them, though, as I couldn’t even pronounce my own name correctly either at the time. Teachers and students would ask me if I had a nickname they can call me by as my name was so ‘difficult’, and I first used to recite my daak naam, only to learn this nickname did not correspond to the nickname the institutions were referring to.

This struggle continued all throughout my life, especially as other nicknames continued to be applied to me, until I applied one to myself and stuck with it. Loudmila, Mila, and Ivana have all had their fair share of exposure to the Bengali culture, and I loved having my daak naam, especially as it isn’t embarrassing, because it made me feel closer to being Bengali; I had one of our Bengalis’ distinctive qualities, and it made me proud. But, did others feel this way as well? What about those who don’t have a daak naam, do they feel left out?

Putting modeling aside, my coexistent passion for [socio]linguistics galvanized my analysis. Initial data was obtained from 42 individuals ranging between the ages of 17 to 34, with the mode age being 20 years, followed by 21 years. This data consisted of the responses to a 13-question survey conducted and distributed online consisting of general questions regarding if one has a daak naam and how they feel about their culture in relation to having a daak naam in general. After leaving the survey open for a week and a half (as the assignment was due soon), the feedback was analyzed and certain individuals were invited for an interview. Of the sample (42 total), 4 were chosen to be interviewed, two having nicknames and two who did not. The survey participants consisted of personal friends, acquaintances and strangers, an attempt to aavoid bias within the study. Respondents were given a brief synopsis of the study and were told to answer as honestly and accurately as possible as their responses would not be judged by me prior to its commencement.

Of the 42 respondents, 34 of them did have a daak naam while only 8 did not. For those who have Bengali nicknames, 73.8% of people said they used it at home, 76.2% said with their families, and 35.7% of people said with friends outside of school. The major switch from using a nickname and an official name between friends from professional settings versus casual was interesting and a scenario I was expecting.

The questions on this survey were designed to be general for the participant, while indirectly answering the questions I was intending to study. I purposely manipulated vagueness to allow for the interviews to be more in-depth narratives about these questions, while also allowing me to make general connections. When asked which name the respondents preferred to go by more often, 26 of the participants said that it depended on the situation, while 14 stated their first names. This was the clearest indicator to me that there most definitely is a social factor to take into consideration when introducing oneself and then committing to that role with these people.

The Likert scale questions (scale from 1-5) were designed to see where one’s opinions lie when it comes to names and Bengali culture. Those who did not have daak naams said that having one would make them feel closer to their culture (3 on Likert scale), but then not having a name does not make them feel any farther away from it (1 on Likert scale), which seemed a bit contradictory to me. This was tested a bit more when I interviewed the 2 respondents with no daak naam. One stated that due to having a very Bengali first name, along with his parents’ decision to not give a daak naam to be ‘more American‘ did not make him feel compromised as his first name was ‘Bengali enough’.

There was a clear divide between if having a daak naam is like having a second identity. But, the consensus was that when putting this face on (daak naam), their social practices change. One participant even stated that having a separate identity is a potential benefit involving a sense of closeness, even to the Bengali culture: “Yeah, I actually do think that having a nickname has an effect on how Bengali someone feels and how close to the Bengali culture they are. I feel like having a nickname helps you feel more connected because that’s how someone might be called growing up, and experiencing more and feeling more attached to their parents’ culture I’d say.”

This study is simply a start for further research into this topic, one I intend on reviving. The biggest issue with my preliminary study was the lack of time and respondents in that short span of time. These participants were mostly from the Queens, NY area as well, so it is still highly biased within the low sample count. With a platform as great and wide as BoNY, we can create an even bigger sample, to have more concrete conclusions regarding this sense of having multiple identities corresponding with our multiple names. With your interest and assistance, a new and improved research study can be conducted, with hopes of publication. The topic of daak naam’s is one that is not specifically targeted in the world of linguistics. I aspire to add more diversity to the worldwide studies being conducted on such matters while also shedding more light on our Bengali community.

The link to the full study (along with all the survey questions asked and answered) can be found on my Instagram page: @loudmilahassan or directly through here. If interested in restarting the study, please do reach out! I’ve also performed a study on the transition from speaking Bengali to Banglish if you’re also interested in looking into that as well!

Read More

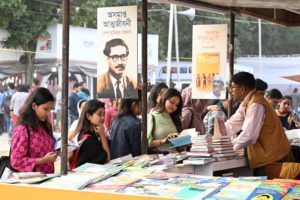

The Legacy of Boi Mela

Every year in February, the month-long national book fair welcomes...

Read MoreMillennial Amma: How to Explain a Global Crisis As a Parent

Rumki Chowdhury shares tips for how to talk to children...

Read MoreBegum Rokeya’s Millennials

A tribute to a pioneering Bengali feminist writer, educator and...

Read More